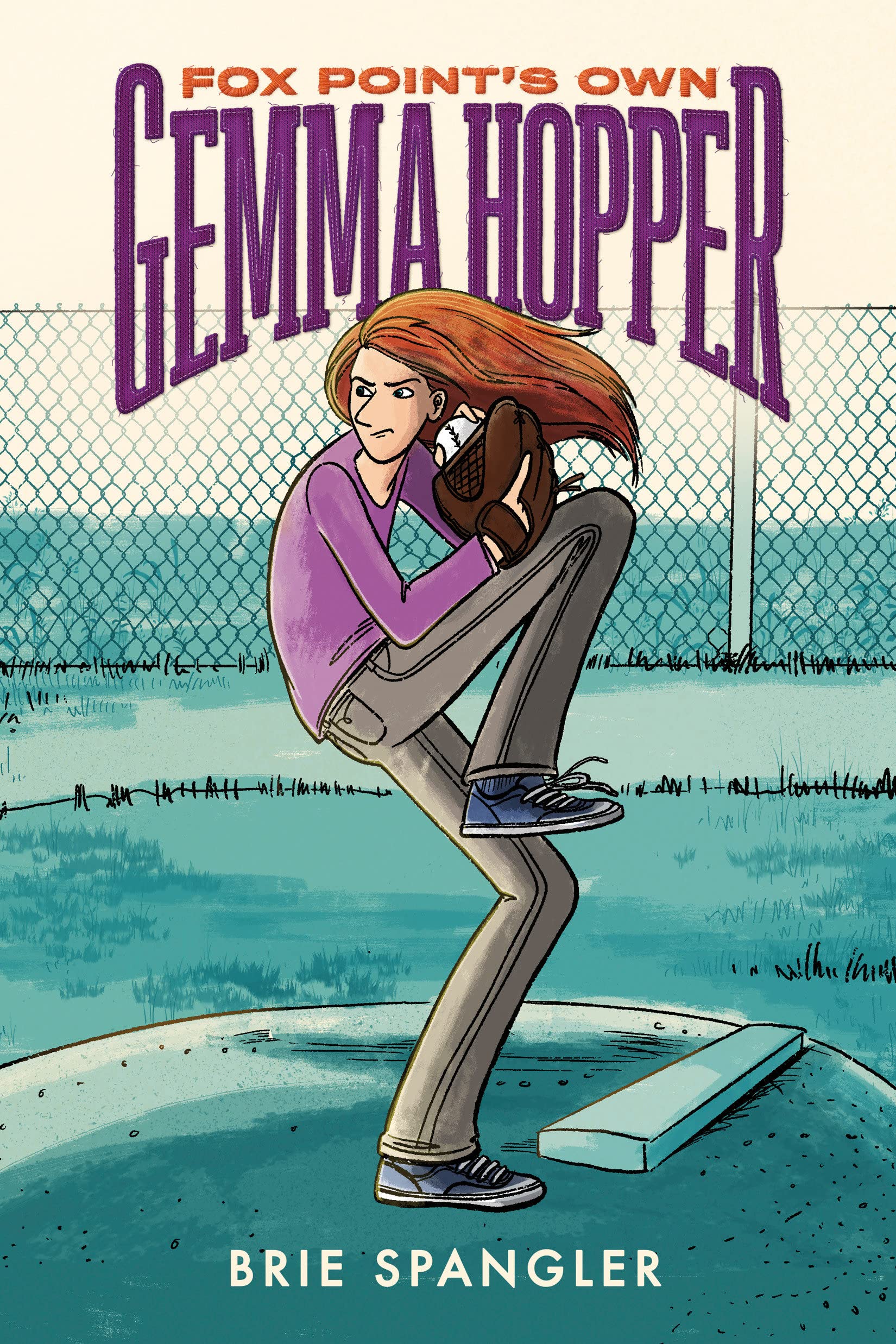

Family strife often forms the basis for a story, and the recently released graphic novel, Fox Point’s Own Gemma Hopper does it with a baseball flavor. Read on for the review.

Family strife often forms the basis for a story, and the recently released graphic novel, Fox Point’s Own Gemma Hopper does it with a baseball flavor. Read on for the review.

Back Cover Blurb

In their tiny corner of Fox Point, Rhode Island, Gemma Hopper’s older brother, Teddy, is a baseball god, destined to become a Major League star. Gemma loves playing baseball, but with her mom gone and her dad working endless overtime, it’s up to her to keep the house running. She’s too busy folding laundry, making lunches, getting her younger twin brothers to do their homework, and navigating the perils of middle-school friendships to take baseball seriously.

But every afternoon, Gemma picks up her baseball glove to pitch to Teddy during his batting practice–throwing sliders down and away, fastballs right over the middle (not too fast or he’ll get mad), and hanging curveballs high and tight.

The Review

13-year-old Gemma Hopper has it rough. She has to take care of her family in her mother’s absence while her older brother Teddy, a 14-year-old baseball talent, has been chosen to play with a prestigious travel team. Gemma likes baseball, too, but will she ever get her chance to shine?

I generally don’t have a problem with characters who have challenging circumstances. However, Spangler dumps so much onto her main character that watching Gemma go through her daily life is unpleasant. Her mother’s been AWOL for a year, and Gemma’s expected to do all the housework and parent her younger twin brothers, who don’t lift a finger to help. Her blue-collar dad is always working, and on the rare occasion he’s home, he only has eyes for his golden baseball child, Gemma’s older brother Teddy. Teddy also happens to be good-looking and the most popular boy at Fox Point Middle School. Meanwhile, Gemma has plain looks and gets mocked for her six-foot height. She only has one friend, and that friend is not beneath trying to use her to get in with the popular crowd.

In short, her home life sucks, her social life sucks, and even though she’s working like crazy, no one appreciates all the things she does. There’s a lot of pent-up anger and frustration in Gemma, and it gets laid on so thick, it’s hard to believe she has any bandwidth to humor Teddy’s demands for batting practice.

Ultimately, this is a story about family. While the Hopper family is obsessed with baseball to the point of naming their children after professional baseball players, this is not really a sports story. For all the hype about Teddy’s talents, we never see him in an actual game. He was part of the local Little League and has been chosen for a prestigious travel team, but we only ever see him and Gemma playing baseball. And when he shows off to his adoring crowds, he is hitting “homers” to pitches that he calls.

However, the Hopper family dynamics are really whacked. It’s never explained why the mother leaves. There’s a vague sense of shame about it, but no one resents her for it, nor is the father blamed for it. The dad is pretty much an absentee parent, and even though grandparents are around, they’re not helping. A charitable Mrs. Curran is helping out with childcare, but the grandparents don’t even respond to emails. And the only one doing household chores is Gemma, who feels obligated to hold everything together and do it with a smile.

Certainly, there are thankless families out there, but Gemma handles it more like an adult working mom than a 13-year-old dealt a bad situation. For instance, her younger brothers only ever play video games, and she never asks them to help out. And when she yells at one of them for making a mess, Teddy yells at her. But instead of yelling back at all of her brothers for making her life difficult, she feels so guilty that she runs out of the house. She’s not getting much love or appreciation, so I don’t see why she’s going out of her way to spoil her younger brothers (elementary school kids are capable of doing chores too!) or spend her very little spare time helping Teddy with his practice.

With family adults mostly out of the picture, Gemma’s interactions are primarily with Teddy, and those feel less like sibling interactions and more like a post-honeymoon phase married couple struggling to get by and get along. The narrative does a decent job of showing the pressure Teddy carries. Both siblings seem to understand that the family’s financial health depends on his future athletic career, which is why he is excused from household responsibilities. However, Teddy relying on Gemma as his personal pitcher just seems odd. Baseball is a team sport with A LOT of players, and Teddy, who participated in the local Little League, should have other peers to practice with. But no, his overworked younger sister is his only choice?

Also, a big deal is made about how the entire family is baseball obsessed and how Gemma learned to pitch from her grandfather. But if that was the case, why was Teddy the only child to do Little League? Why weren’t both of them in sports? The mom has only been gone a year, so Gemma should’ve had the same opportunity. The Gemma-does-all-chores could be a sign that they have a family culture where boys play sports while girls do housework, but that runs contrary to the grandfather teaching her how to pitch.

Eventually, Gemma gets recognized as an athlete in her own right, and she realizes that her mother will never return. This brings closure to Gemma’s story, but I didn’t find it that satisfying. There’s a supposedly tender parting scene between Gemma and her dad, but it gave me a bitter taste because she only receives his affirmation and recognition AFTER she is recognized as an athlete, not before. It is also only then that the father makes arrangements to take care of the household and the younger children (so that Gemma can go to Florida for baseball training), even though he could have done it sooner and lessened the burden on his daughter.

The book is printed on glossy stock, so it’s pretty heavy. The title page and author afterward are printed in color. The bulk of the graphic novel is black and white with a bluish-gray shading, and just a few pages have drawings printed in a reddish-brown.

In Summary

Fox Point’s Own Gemma Hopper looks like it’s a sports story, but it’s not really. It’s more about the family drudge finally having her day in the sun, where her chief rival is her good-looking, popular, golden-child brother. While I’m all for family drama, this baseball-themed sibling rivalry stacks way too much against Gemma, and I get tired of her sour face real fast.

First published in The Fandom Post.

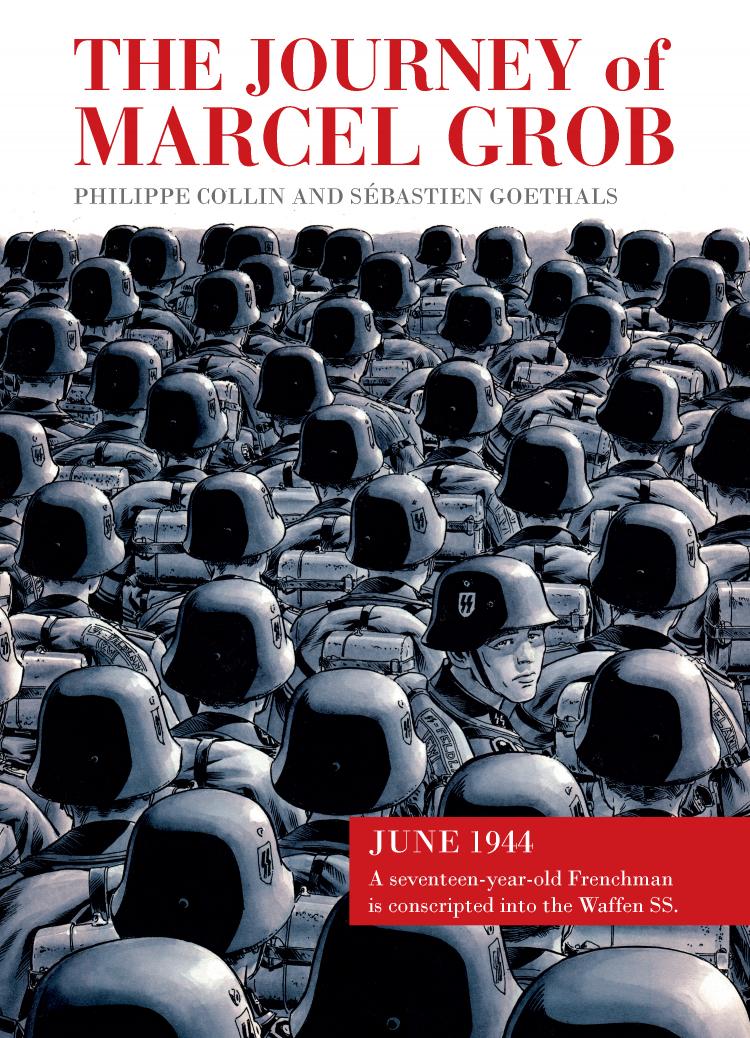

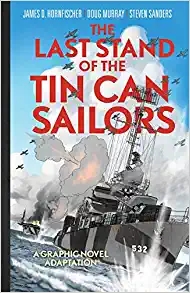

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across

I never had much interest in war narratives until I came across